How to: World Record in Texas

Map shows the traces of flights made by our expedition between June 10- 25, 2023. Texas offered flyable (but not record) conditions every single day. The good roads and availability of small public airports for towing gives great flexibility to get into the air at the right place at the right time.

Among the goals of our Texas expedition was to scout out the possibilities for record setting. So, how suitable is Texas?

The Bottom Line up Front

Record flights require record conditions. The likelihood of getting such conditions in a random 2 week window is low.

A record attempt in Tx has significantly better chances of success if the timing is flexible. Under the assumption that the macro weather situation can be predicted ~1 week ahead, an trip can be set up in time.

From June 11-25, we had a stable layer above Texas. This reduced the thermal activity and prevented early starts and late landings. All other conditions for flying far were given.

What Texas offers in favor of long flights

Terrain: Texas is mostly flat, with few obstacles. This allows flying with a reasonable degree of safety even in strong wind. More specifically, we scoped out

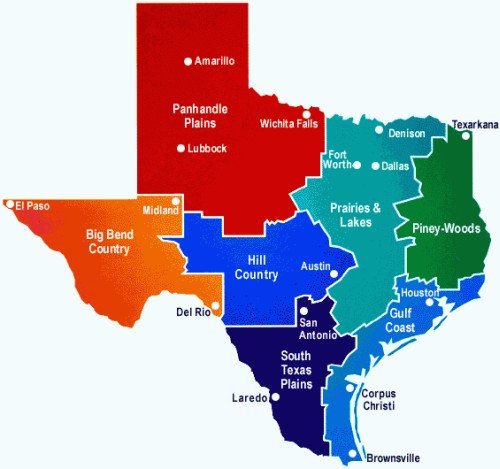

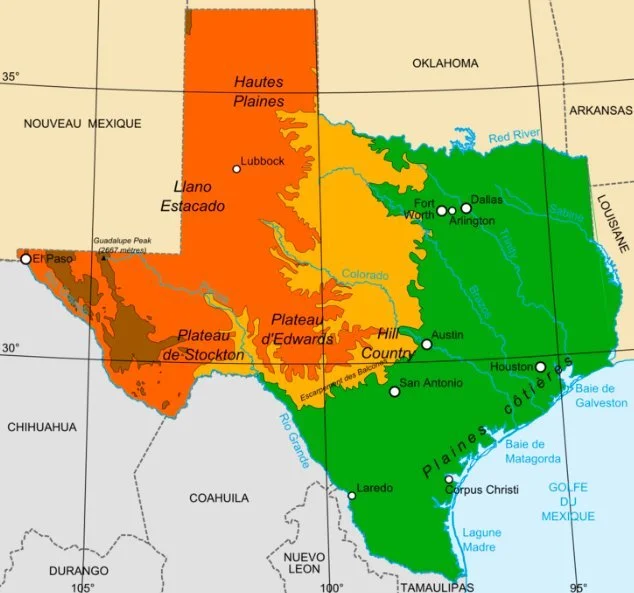

The Panhandle Plains (980 m ASL, see lower left map) can be flown even with significant wind. The area is very flat, open farm land, offering plentiful unproblematic landing options. On its Eastern fringe, a few shallow canyons carve their way into the plateau (see lower right map). While these canyons are typically both landable and accessible for retrieve, strong winds will cause lee turbulences. In this geography we launched from

Levelland, TX (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:rchandra/21.06.2023/16:57),

Quannah, TX (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:Timoleo/19.06.2023/16:37), and

Woodward, OK (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:rchandra/20.06.2023/16:54).

We were able to achieve XC progress speeds of almost 50 km/h and higher.

The South Texas Plains and Gulf Coast are extremely flat too, allowing flying with strong wind. In Refugio, we were able to fly with a thin safety margin despite ground winds gusting well above 40 km/h, reaching higher values further up. Unfortunately, a lot of the land is covered with shrubs (think thorns, think Mesquite). This is not necessarily a safety concern: These shrubs don’t create dangerous lees, they will however destroy a glider. Also, a lot of the properties are surrounded by fences and locked gates. Again not a safety concern, but more tedious retrieve, which may lead pilots to follow roads and thus be slower. In this geography we launched from

Hebbronville (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:osimo/12.06.2023/15:25),

Refugio (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:rchandra/18.06.2023/15:16), and

Cotulla (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:Timoleo/13.06.2023/16:12).

Zapata would be a further option, provided the wind does not lead trajectories over the border or Laredo airspace.

Big Bend Country has some mountains (see lower right map), but is flat and wide open otherwise. We flew with strong wind, achieving XC progress speeds of almost 50 km/h and higher. This terrain is very remote, and we tended to follow highways, especially further West. In this geography we launched from Van Horn (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:osimo/16.06.2023/16:45).

Hill Country has nasty geography for XC flying. These ridges and canyons will have nasty lees if winds exceed 15 km/h. Bracketville is one of the more benign entries into Hill Country (https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:rchandra/22.06.2023/16:41).

Wind: As mentioned above, the terrain allows flights even in strong wind. Unlike the Brazilian Sertao, we experienced good wind gradients with manageable speeds near the ground and higher speeds up high.

Flexibility in launch sites: Even small Texan towns can have a public airport, often with runways of 1 mile length. Select where you want to fly, and find an airport. Look it up on http://www.airnav.com/airports/get to obtain it’s coordinates, elevation and runway lengths. If it’s use is “open to the public“ there should be no issues in launching from it, provided its not too frequented (See Airport Operational Stats). Note the ATC radio frequency (CTAF). Give the airport manager a call, being Texan and being friendly is probably a good idea. File a NOTAM for the day you will be flying and you’re good to go.

Ben Parker and his buddy were our tow techs, who doubled as retrieve drivers. For this kind of work, you really need a tow tech who knows exactly what they’re doing, This person is Ben. A Texan himself, he handled all communications with locals (airport managers, land owners) expertly. Ben also sports a heavy duty offroad e-unicycle, with a range of +100 miles. This allowed him to reach stranded pilots even when access gates were locked, to help take the glider off the pilot’s back.

Fast roads: Texas is crisscrossed with a web of highways allowing you to cover distance faster while driving than in Brazil.

San Antonio International Airport is probably the best place to fly into.

What about the lapse rate?

The two weeks we were in Texas presented themselves as stable. An inversion in the lower troposphere dampened thermals, preventing early starts and late landings:

The coastal plains started being thermally active reasonably early, but the lift stopped a few hundred meters above ground - too low to fly fast. Days started out cloudy but became blue around noon.

Higher up on the plateau, we often had to wait until past 11:00 am for the ground inversion to be cooked through. Despite the ground inversion, there were days where the lapse rate above 3’000 m was too aggressive, causing overdevelopments and thunderstorms in the afternoon.

Previous expeditions by XC trophy hunters in the area (including by Donizete Lemos, Rafa Saladini, and Gavin McClurg) turned up empty handed too, suggesting that you are unlikely to encounter a record day in a pre-determined window of two weeks. That said, we know from the record holders (Sebastian Kayrouz, Will Gadd, Larry Tudor, Robin Hamilton, Jonny Durand) that Texas offers record days with early take-offs, late landings, and fast conditions in between:

Early launching: Texas record holders listed above typically launched between 9:30 and 10:00 am. The hang gliders launched via aero-tow, making rapid relaunching difficult and creating a huge incentive to not launch too early. The paraglider record were mainly solo operations rather than team-flying efforts, which could probably launch earlier.

Late landings: Many locals have confirmed that good days are buoyant way into the evening. Unlike Brazil, where civil twilight ends 20 minutes after sunset, Texas offers 30 minutes.

Fast conditions: Among the people I’ve spoken with, there is no consensus on the necessity of a dryline. It does appear though that cloud streets (which readily materialize in Texas as can be seen on satellite images) are a must for long flights. Anecdotally, favorable conditions are created by a cyclone over Louisiana, clearing out stable layers and inducing a southerly flow (see synoptic charts below for Keyrouz’ record flights, from National Weather Service Archives).

Record conditions as described are unlikely to randomly appear in a given time window, but given that the Louisiana cyclones are pronounced - in the cases of Keyrouz’ record flights above they were named tropical storms - they should be predictably with sufficient advance notice to put together a fast response team.

What a record attempt on-call might look like

The National Weather Service provides synoptic charts 7 days out: https://www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov/medr/medr.shtml and https://origin.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov/cgi-bin/get_medr.cgi

Assuming we record conditions were to materialize in a 3-day window centered on July 1, 2024, the sequence of actions might be the following:

Beginning of season (May): Organize local tow techs, winches & other equipment, figure out Visa/Esta issues

D-7, D-6 (June 24-25, 2024): Long term synoptic charts indicate a cyclone forming near Louisiana in 6-7 days: Inform all team members, explore on-site availability of tow techs & winches.

D-5 (June 26, 2024): Persisting forecast of cyclone over Louisiana in 5 days: Book flights & rental cars with tow hitch. Ensure that tickets can be cancelled within 24 h if need be.

D-4 (June 27, 2024): Commit based on weather forecast in 4 days. Confirm availability of tow techs, winches, vehicles, equipment. Pack.

D-3 (June 28, 2024): Departures from Europe, arrive in San Antonio, rent cars, stay in hotel.

D-2 (June 29, 2024): Drive to rally point (e.g. Uvalde, Hebbronville, Zapata, Cotulla). Meet with tow techs. Check and finalize equipment. File NOTAMs. Study trajectories and prepare declared goal.

D-1 (June 30, 2024): Study trajectories and declared goal according to FAI. First record flight attempt.

D-0 (July 2, 2024): Study trajectories and declared goal according to FAI. Second record flight attempt.

D+1 (July 2, 2024): Study trajectories and declared goal according to FAI. Third record flight attempt.

D+3 (July 4, 2024): Catch flights back to Europe

The window of record conditions centered around June 19, 2021, started to become visible in forecasts 6-7 days out. That charts above show the forecasts for June 19 as they presented themselves on June 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and the actual chart of June 12. June 12’s forecast already predicts a low, which deepens in June 13’s forecast.