On Lightning and Gust Fronts

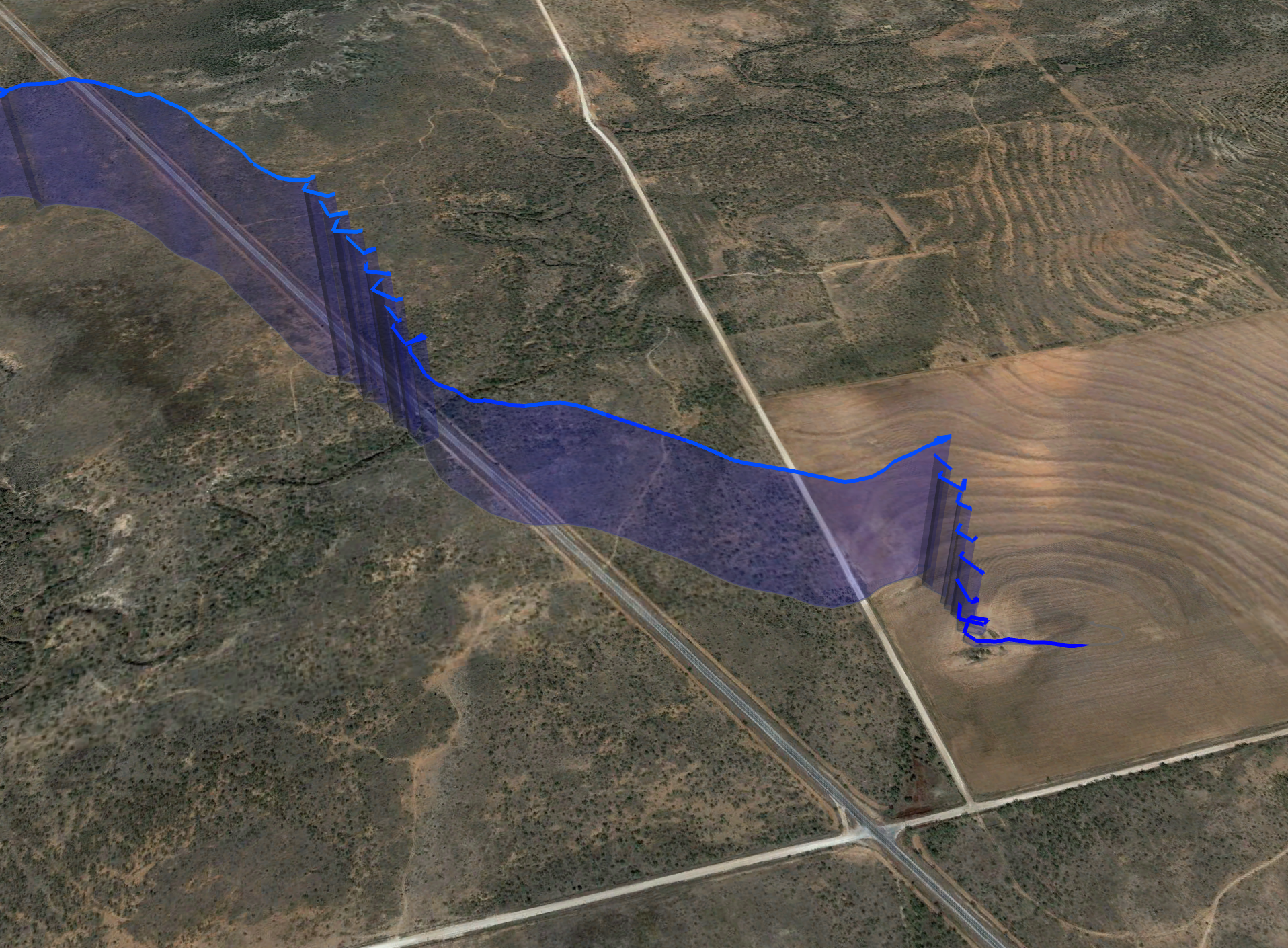

The sky as it presented itself after landing.

Texas taught me about overdevelopments (OD). I’ve had to revise my rule of “as long as there’s blue sky above you, you’re fine”.

On this particular day, the lower atmosphere was rather stable, while the lapse rate above 3000 m was pretty steep. We expected the day to start late, but overdevelop. The forecast had predicted thunderstorms.

Follow the flight here: https://www.xcontest.org/world/en/flights/detail:rchandra/21.6.2023/16:57

In the early afternoon I saw a first cloud dragging a small veil of rain below it. Nothing unusual, I felt far from threatened.

Pictures above, taken by Sebastian Benz: As I approached the cloud it was isolated and surrounded by blue (left). Only 25 minutes later it had become a thunderstorm, with lightning and cold air outflow (right).

Further down the course, I glided towards a nice cumulus (see picture above left) above the airstrip of Colorado City. It looked safe to me: not too tall, isolated, surrounded by blue, no signs of rain. I arrived below it around 900 mAGL and settled for a slow 1 m/s climb to clear me over the upcoming forrest. The cloud had grown and I noticed a splotch of rain under the same cloud further to the west. Few minutes later, Sebastian radioed me, telling me the rain had caused a cold air outflow and storm gusts in the town ahead. I took this seriously, Sebastian is one of the most competent XC pilots I know, and not prone to exaggeration.

Mere minutes later, I heard thunder. My thermal had accelerated to 4 m/s. I decided to leave it halfway. Then I saw lightning. Danger close lightning - the length of the lighting bolt comparable to my distance to it. I pushed speed bar to get away, continuing to climb. Two further lightning bolts, one close, one far.

I pushed speed bar as far as I dared in the boisterous climb. I had observed the storm getting pushed WSW and I was pushing due south, averaging 68 km/h with tailwind. I was outrunning the storm. Sebi radioed me again, warning me of a gust front and nasty conditions on the ground. “Rico, be careful, that next cloud will likely pop too. If you have doubts, consider landing”.

The gust front can be seen as an orange hue above the horizon, caused by the red earth lifted into the sky. Picture by Sebastian Benz

I kept hauling south, increasingly pushing bar. I looked back over my shoulder and saw the gust front: a red wall of dirt, about 60 m tall, and several km wide, chasing after me. At that point I decided it’s not worth the risk. I’td try to land before the gust front.

Gust fronts like this one are caused by cold air outflow. A fair amount of a rain drop’s water content evaporates on the way down, consuming energy, supercooling the surrounding air. This air crashes to the ground and spreads, whirling up the red dust to become visible. Besides being strong and turbulent - unthinkable to land a glider in a controlled manner - this cold gust front wedges itself below the hot ambient air, setting off cascading thermals in a chain reaction. Not ideal if you’re trying to land fast.

I cranked my Enzo into a tight spiral dive to work myself down through the rising air. I spiralled closer down than I ever have, leveling off with just enough height to turn into the wind and land. Five minutes later, the gust front crashed over me.

Deep spirals in rough air to get down before the gust front hit.

Lessons learned

It is not uncommon for lightning & thunder to appear with even minor precipitation

A cold air outflow destabilizes and can lead to a domino effect of surrounding clouds boiling over

The rule of thumb “if there’s blue sky above you, you’re safe” needs caveats:

a) provided you’re out of range of the cold air outlfow, and

b) once there is even a bit of rain, there can be lightning.

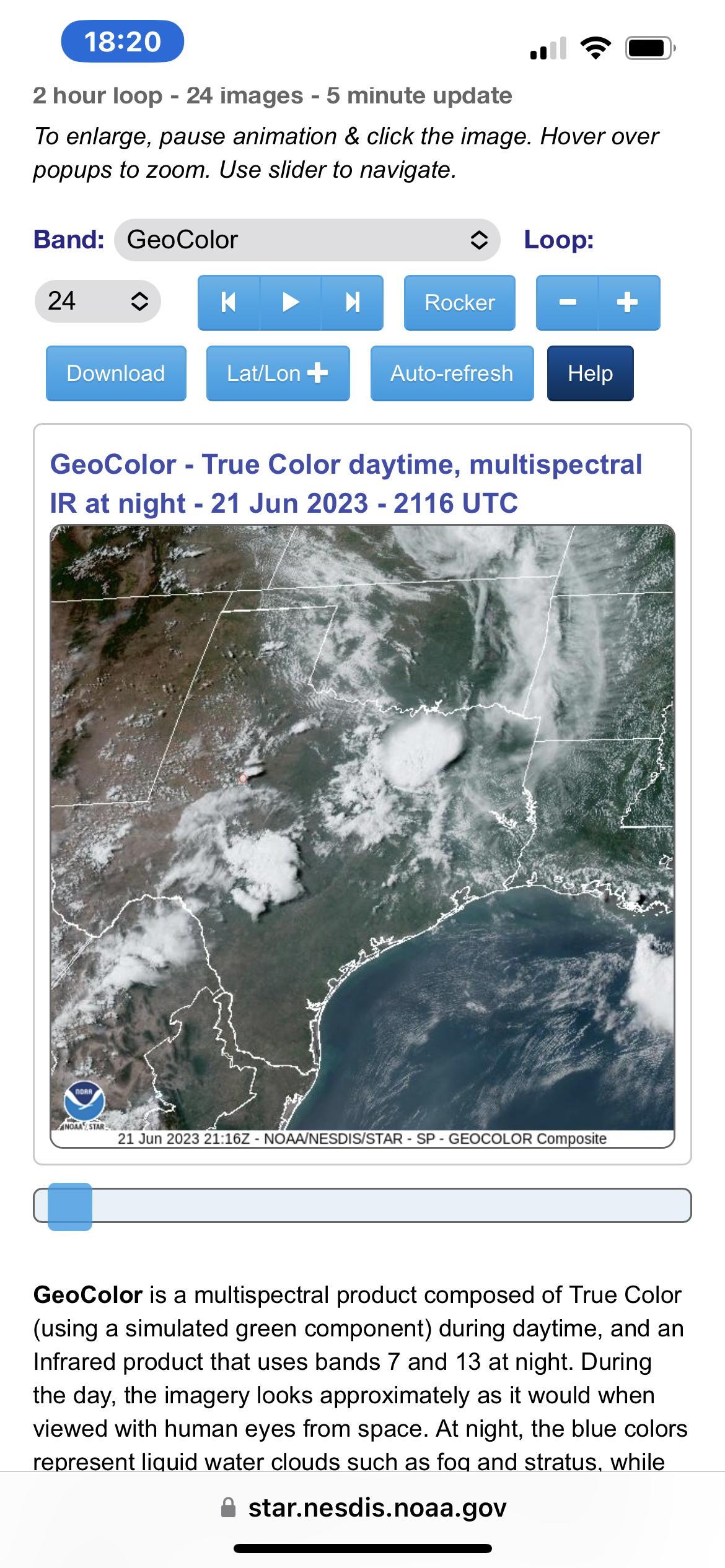

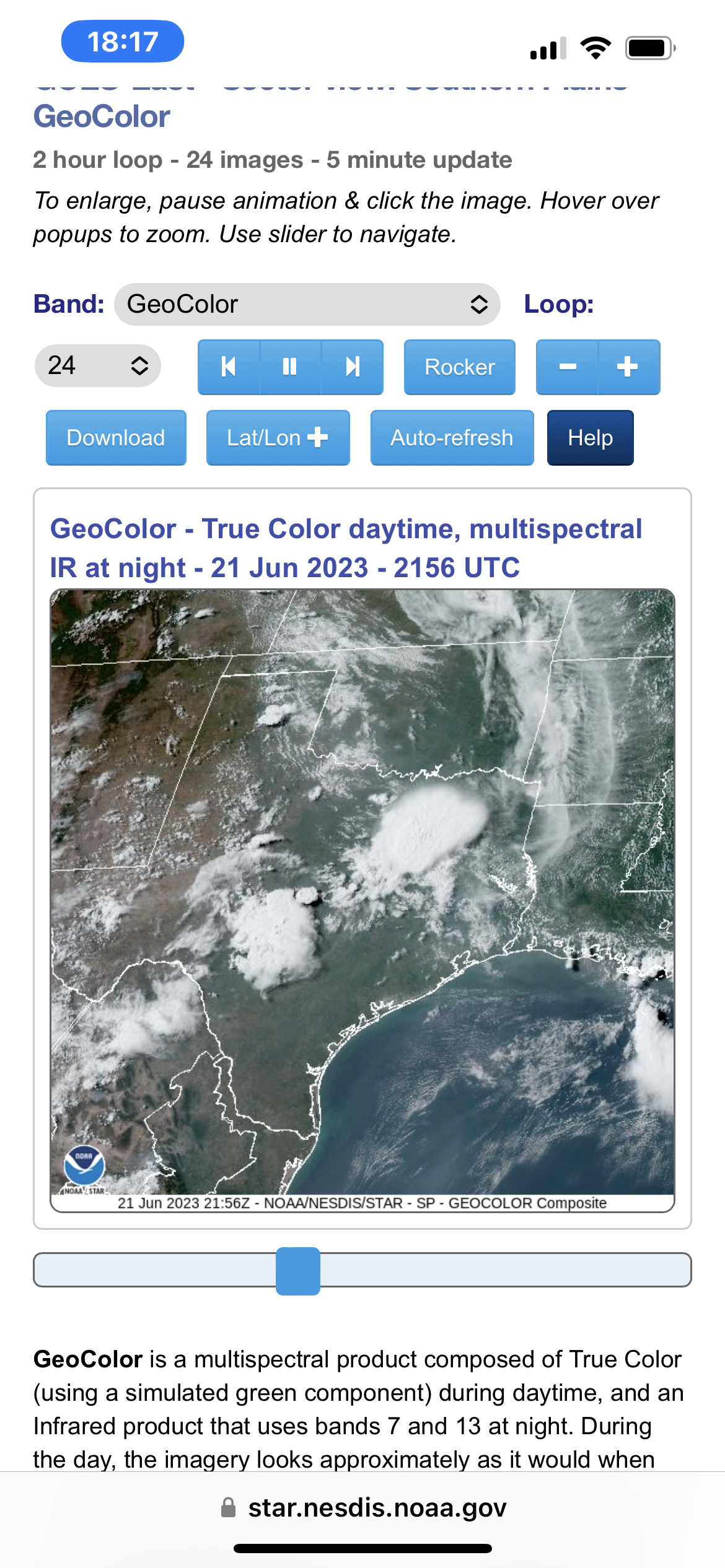

Left: Satellite image marked with a small red circle to approximate my position at the time. Right: 40 minutes later.